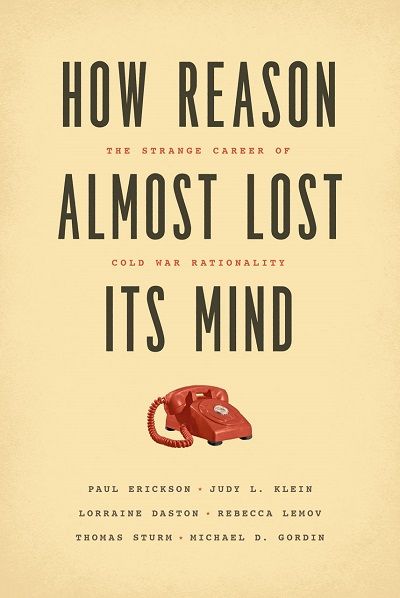

“It was three stories underground in Nebraska. It had no numbers to dial. It was how the Strategic Air Command would start bombers on their way to Moscow,” said Judy Klein, professor of economics at Mary Baldwin, referencing the famous Cold-War-era “Red Telephone” on the cover of her new book.

“It was three stories underground in Nebraska. It had no numbers to dial. It was how the Strategic Air Command would start bombers on their way to Moscow,” said Judy Klein, professor of economics at Mary Baldwin, referencing the famous Cold-War-era “Red Telephone” on the cover of her new book.

How Reason Almost Lost its Mind: The Strange Career of Cold War Rationality — co-authored with Paul Erickson, Lorraine Daston, Rebecca Lemov, Thomas Sturm, and Michael D. Gordin, her colleagues from the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin and published by The University of Chicago Press — examines how top thinkers redefined rationality into a more optimizing, algorithmic, and mechanical tool, aiming to tackle Cold War-era problems. Klein and her fellow authors investigate what it meant to be rational at a time when nuclear war was just a phone call away.

“We are looking at how the social and behavioral sciences played a role in research for the military,” Klein said. “The title refers to the development of an algorithmic view of rationality that involved a lot of loss of judgment, coming in the context of ‘Peace is our profession’ [the official motto of Strategic Air Command] when many military and government officials thought they had to increase armaments to promote peace, according to the theory of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD).”

Researchers and scientists from many different fields hoped to find reliable safeguards to stave off the threat of nuclear war and ensure that decision-makers followed rules of rationality usable in — as the authors write in the book’s abstract — “a mad, MAD world.”

“Military needs shaped a new view of rationality — an eagerness to let computers take over the decision-making process,” Klein explained.

Each author approached the theme of Cold War rationality from a different disciplinary perspective. Klein contributed the most expertise to Chapter 2, “The Bounded Rationality of Cold War Operations Research.”

“You can tell there’s a lot of economics to it,” she laughed. “The theme of Chapter 2 is that there was so much pressure on the military to cut its budget after World War II (during the war the military consumed more than half of all goods and services in circulation) that it turned to an algorithmic view, to the promise of digital computers and mathematical models of decision-making as ways to save money.”

Chapter 2 begins with the Berlin airlift (1948–49) and looks at how, during the airlift operation, the United States Air Force tested methods developed by its Project for the Scientific Computation of Optimum Programs (or Project SCOOP, first started in 1947). During this project, applied mathematicians and economists had created mathematical models and algorithmic solutions for digital computation that aimed to rationalize and optimize Air Force activities. The application of these models to the real-time situation of the Berlin airlift, however, showed that a lack of computing capacity prevented them from optimizing operations effectively. They were, literally, ahead of their time.

“Herbert Simon of Project SCOOP realized that rationality was limited by computational resources, what he called ‘bounded rationality,’” said Klein. “They didn’t have the computers needed to fully utilize these mathematical models until after 1952. The linear programming that he came up with, however, is still widely used throughout business and government.”

In keeping with the book’s theme, the authors used a randomizing computer program to determine the order of their names on the cover. Klein emphasized that the book is a collaborative work that began in March 2010 when a group of scholars gathered in Berlin for a workshop on “The Strangelovian Sciences” (referencing the film Dr. Strangelove, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb) at the Max Planck Institute. Six members of that original group returned to Berlin during summer 2010 to continue their discussions and begin writing.

“We all worked together,” Klein said. “It was a wonderful process, and we got to spend a summer in Berlin, which was a great place for studying the Cold War. The Max Planck Institute for the History of Science supported our project.”

The book garnered a review in Science magazine about which Klein said, “I was pleased that the book was reviewed, and the reviewer pointed out some things that were left unresolved in this book that maybe will yield new work.”

Klein now plans to return to her research on another book — one on which she has been working for almost 10 years — that was supported by an Institute for New Economic Thinking grant in 2011. Klein looks at how work for the military in World War II and the Cold War yielded applied mathematical models that then went on to have a huge impact on modern economics. She explores how U.S. Military needs induced a mathematical modeling of rational allocation and control processes while simultaneously binding that rationality with computational reality. Modeling strategies — to map the optimal to the operational — ensued and eventually became a key driving force to the development of macroeconomic theory.

“The Air Force and the Navy in the 1940s and 1950s ended up funding a lot of economic research,” she explained. “During World War II, the economists who were hired by the military had statistical backgrounds, which was relatively uncommon in the discipline at the time. The military wanted applied mathematicians to help them economize, and this selection process ended up emphasizing statistical backgrounds and changing the whole track of becoming an economist. Now it is a very statistical/mathematical discipline.”