Jelani Meyer ’22 cued the opening music for 2019’s Kwanzaa at MBU celebration on his laptop — and nothing happened. His heart raced. About 50 participating first year classmates and a standing-room-only crowd of more than 400 students, faculty, staff, alumni, and #MBUfamily members bristled: Why hadn’t the ceremony started?

The tech savvy freshman scrambled to troubleshoot. He was the DJ; everyone was counting on him. Meyer kept his cool and fixed the problem within minutes. He watched awestruck as music filled Hunt Dining Hall and a dozen costumed peers paraded down the aisle, launching into a dance sequence based on Marvel Studios’ Black Panther that merged African folk traditions with modern movements.

The group performed before a table-topped stage overflowing with harvest themed decorations. Their dance was an interpretive expression of one of Kwanzaa’s seven motifs — unity (umoja), self-determination (kujichagulia), collective responsibility (ujima), cooperative economics (ujamaa), purpose (nia), creativity (kuumba), and faith (imani). Honored seniors and alumni wearing formal African garments like iro ati buba, agbada, kitenge sets, and duku head scarfs cheered them on from a special audience section.

Students were responsible for nearly every element of the production. They’d choreographed dances, selected music, written songs, composed poems and short plays, designed and altered costumes, handsewn ceremonial outfits and ornamental drapes from imported African fabric, created and arranged customary decorations, secured rehearsal space, scripted and filmed invitation videos, and more.

“I had this realization about how powerful this experience had been, about how we’d been building up to this moment since the beginning of first semester, about how working on Kwanzaa had changed us,” said Meyer, now a senior. “I was looking around at everything and everyone, and just feeling so proud of what we’d accomplished.”

Work on Kwanzaa begins before the first day of classes for some students, and shortly thereafter for the rest. They collaborate with Chief Diversity Officer Rev. Andrea Cornett-Scott, Office of Inclusive Excellence (OIE) staff, alumni, and upper-level student leaders on early tasks like choosing a guiding theme, surveying talents and skill sets, forming groups, and outlining programming. Next comes curating performances for Kwanzaa motifs, and tasks like preparing costumes and decorations. Weekly rehearsals begin around late October. The cadence increases to three or four per week as the ceremony — typically held in February — nears, with duration often running upward of 3 hours.

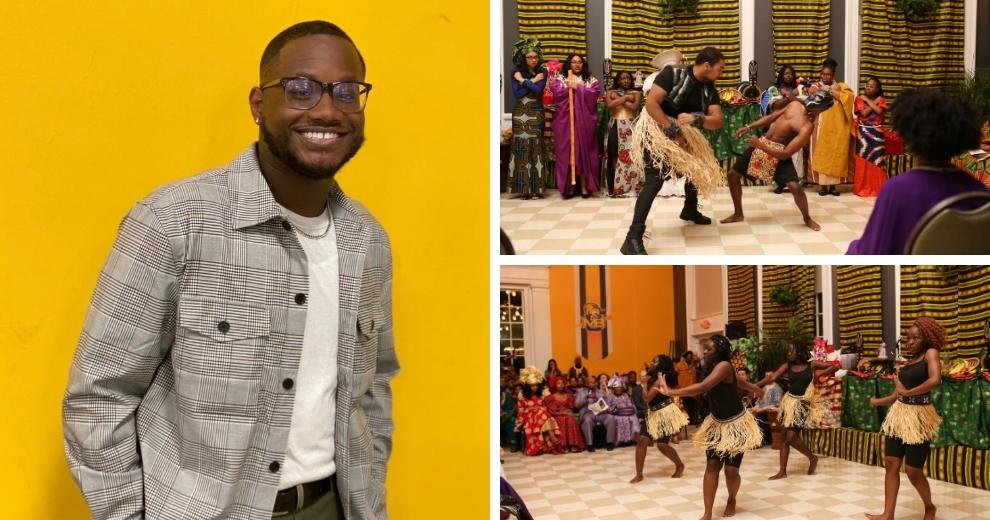

From left: Jelani Meyer ’22 calls Kwanzaa at MBU “a true rite of passage.” Students performing at the 2019 ceremony.

“It’s a big investment,” said Tiffany Foreman ’04, now minister of worship and media coordinator for Gethsemane Baptist Church in Newport News. She participated in Kwanzaa at MBU as a student and has returned to help with nearly every production since graduating. “But the payoff is just over-the-top.”

Foreman and Meyer agree with founder Cornett-Scott: The experience is a rite of passage for first year students and seniors alike.

“You start out as one person and, at some point during that ceremony, you realize you’ve blossomed into this better, more confident version of yourself,” said Foreman. But not only that, “you see you’ve made incredible new friendships — and that if it wasn’t for those friends, you could never have reached this point. That’s when you look around the room and understand: You’re now a member of a community that includes all the alumni that came before you. And every one of them is there because they believe in your ability to succeed, and want you to know they’ll always be in your corner.”

Cornett-Scott calls such epiphanies par for the course: “That experience … it’s the outcome we’re building toward for all of our student participants — and we are very, very intentional about it.”

She’s spent the past 25 years engineering a program unlike any other in the nation. Alumni call it a cornerstone MBU experience. Its success is reflected by boosted retention and graduation rates among full participants compared to other student populations, with percentages skyrocketing to above 90. But Cornett-Scott prefers a different metric: More than 100 alumni travel from all across the U.S. to attend each year. And pre-pandemic attendance among non-student populations averaged above 400 — making Kwanzaa Mary Baldwin’s top affiliate standalone event in terms of engagement.

“Kwanzaa has been one of the best — and definitely most empowering — experiences of my life,” said Meyer, explaining why he thinks alumni support is so high. “It’s something I’ll carry with me forever. So, I know I’ll be back. This isn’t an experience you just move on and forget: You want to pay it forward.”

Students at 2019’s Kwanzaa at MBU posing with alumni “elders,” giving speeches exploring themes, and gathering for a celebration of sisterhood.

Today’s Kwanzaa at MBU is wildly different from its earliest iterations. What’s now the OIE was in its infancy when the program launched in 1997. Black and brown students then made up around 2 percent of the student population — and the inaugural celebration featured fewer than a dozen participants.

But Cornett-Scott was sure it would grow.

“This wasn’t some gimmick designed to try to trick more students of color into staying or enrolling,” she said. “This was an opportunity to bring something I felt passionately about to life. It was a chance to affect real, lasting impacts on the lives of young African Americans.”

For Cornett-Scott Kwanzaa at MBU was equal parts vision, dream, and experiment: It was a proving ground for ideas she’d been developing since childhood, when she first became aware of her own Blackness and Afro-Caribbean lineage.

“I grew up [during the American Civil Rights Movement] going to private schools where I was one of just ten Black students,” she said. It — and the greater U.S. of the 1960s and 70s — was a white-dominated world where Blackness was, at best, systematically cast as ‘other.’ But because her family made a point of celebrating Black history and culture through acts like observing Kwanzaa, “I never felt up-in-the-air about who I was or my self worth; I felt comfortable in my skin and confident about my heritage.”

Attending historically Black liberal arts colleges like Howard University and Morris Brown College reinforced those feelings. The experience also pointed out they weren’t guaranteed: Students of color attending majority white schools often struggled with issues around self perception and identity.

That’s because some families of color avoid discussing heritage, cultural traditions, and issues of race. Scholars, researchers, and psychologists agree that’s a problem: Internalizing avoidance strategies can become a source of debilitating uncertainty for young Black and brown people. To make matters worse, they’re likely dealing with these problems alone — which can create a deep sense of isolation.

Chief Diversity Officer Andrea-Cornett Scott overseeing 2010’s Kwanzaa at MBU ceremony.

For Cornett-Scott, the awareness helped fuel academic interests centered around the intersection of religion, philosophy, sociology, African American experience, and African diaspora culture. Cornett-Scott became fascinated by the roles ritual, rite of passage, family, and community played in instilling positive values within traditional African societies. Also, how ceremonies and ideas morphed to endure the North American slave trade and its aftermath. Her master’s thesis at Payne Theological Seminary subsequently explored African American churches as both repositories and disseminating institutions for Black history and culture in the Americas.

Throughout this time Cornett-Scott often found herself helping younger friends and peers find their place in the college community. It came so naturally, she began to think of it as a potential vocational calling.

“College is a pivotal moment in a young person’s life, and the stakes increase according to their vulnerability,” she said. Eighteen to 20-year-olds are considered adults, but most don’t understand the reality of what that means, much less how to be one. And the problem is often exacerbated among those coming from underserved, low-income backgrounds — particularly if positive role models have been lacking.

“This is the time to help them discover who they are, and what they’re passionate about,” Cornett-Scott continued. “We need to help them cultivate the inner voice that will guide them on their life’s journey and empower them to live a life of meaning, success, and personal fulfillment.”

The interest led to positions developing support services and programming for students of color at Monmouth College and James Madison University. Cornett-Scott’s relationship with Mary Baldwin began in 1996 when she was hired as a religious studies professor and named founding director of what’s now the OIE.

“The beauty of Kwanzaa is that it offers a new dialogue on Black culture, about our positive contributions to the world, and not just the negative stigma of race. It starts us as inventors of civilizations, people who wrote the first basic texts of human knowledge, and so on. It gives us a long memory — a long cultural biography.”

Dr. Adam Clark, founder and co-editor of Columbia University’s Black Theology Papers Project.

Cornett-Scott quickly moved to add a lineup of annual multicultural events. She saw Kwanzaa as both a flagship and proof of concept for future programming like Las Posadas, Latine Heritage Month celebrations, and more.

The week-long secular holiday was devised by renowned California State University Africana studies professor Dr. Maulana Karenga in 1966. It draws inspiration from traditional African first-fruits harvest festivals, and is held from December 26 to January 1. Karenga envisioned it as a vehicle for institutionalizing the celebration of Black family values and cultural traditions in America, and unifying African Americans as a community. Observation includes nightly ceremonial reflections based on (the above-mentioned) seven themes, and culminates in a family or community feast.

“The beauty of Kwanzaa is that it offers a new dialogue on Black culture, about our positive contributions to the world, and not just the negative stigma of race,” founder and co-editor of Columbia University’s Black Theology Papers Project, Dr. Adam Clark told Oprah Daily in 2020. “It starts us as inventors of civilizations, people who first broke from the animal world, spoke the first human truths, wrote the first basic texts of human knowledge, and so on. It gives us a long memory — a long cultural biography.”

Cornett-Scott believed that, done right, Kwanzaa could be a vessel for affecting positive, transformational experiences among young people. One that was so powerful they would, like Meyer, insist on paying it forward to future generations.

“Looking back to my childhood, Kwanzaa brought a very special kind of joy into our household,” said Cornett-Scott, who by 1986 was observing the holiday with her own children — and noting similar positive effects. Kwanzaa is a time “to contemplate and honor where we come from as African Americans. It’s a time to build up our young people by celebrating and affirming our strength, our beauty, our values, our worth.”

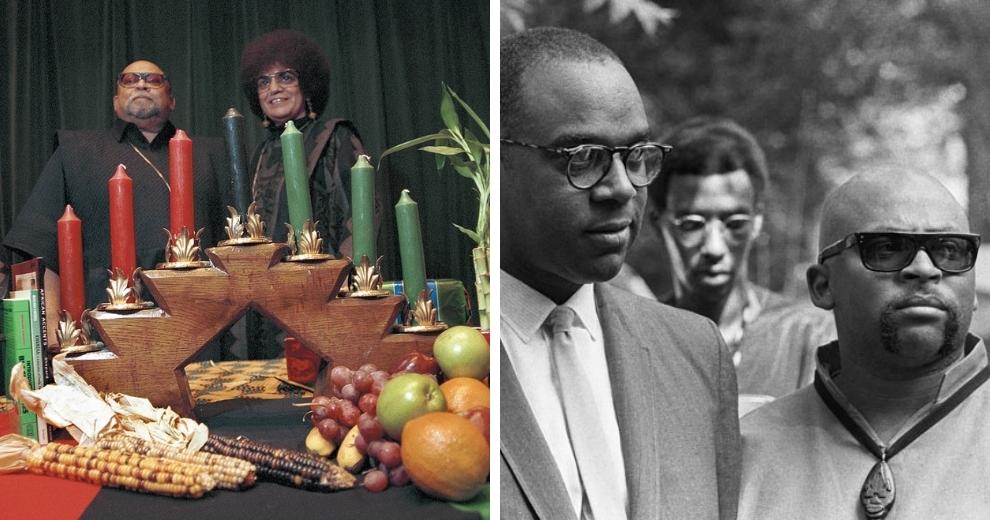

From left: Maulana Karenga and wife Tiamoya celebrating Kwanzaa in 2000; Civil Rights activists Nathan Wright Jr. and Maulana Karenga in the late 1960s.

The Mary Baldwin of the late 1990s had very little diversity. Cornett-Scott argued then what research backed by the American Psychological Association has since confirmed: Racial and ethnic diversity on college campuses brings major benefits for students, faculty, and staff alike.

But that was just one element of her long-game Kwanzaa strategy.

MBU needed programming that would spotlight African American students, help them feel seen, and honor them as an integral part of the greater campus community. And many students of color needed a safe space to explore the concept of Blackness and build confidence around their identity.

But there was also the bigger nationwide problem of wildly higher rates of attrition among Black students at majority white institutions — whom a recent study of U.S. public universities found are 250% less likely to earn a college degree than their white counterparts. The situation is even bleaker for those with low-income, first generation backgrounds: Nearly 90 percent leave school without a degree within six years, and one in four drop out within two semesters.

The net effect is devastating:

In terms of earning power, U.S. bachelor degree holders make about $900,000 more in lifetime income than high school graduates, or about 75% more money annually. Meanwhile, Black families possess less than 15% of the median wealth of white families, and are three times less wealthy than Hispanic families.

“But this is about more than dollars and cents,” said Cornett-Scott. It’s about helping students find a way to earn a living that brings a deep sense of meaning, accomplishment, and self-satisfaction.

The importance of the above has been made abundantly clear by a wave of new studies showing a strong correlation between greater happiness and higher levels of education.

“With more education, people are more likely to be able to do the things that give their lives purpose,” developmental psychologist and Claremont Graduate University associate professor of psychology Kendall Cotton Bronk told CNBC in a 2021 interview. “Studies repeatedly find that individuals with a sense of purpose in life tend to report being happier, or more hopeful and more satisfied than individuals that don’t have that.”

Students say Kwanzaa at MBU is a joyous and emotional event. The annual celebration has grown to include upward of 500 attendees and participants each year.

Cornett-Scott wagered that an unparalleled combination of hands-on mentorship, institutional and peer support, and special programming could transform MBU into an exemplar for helping students of color succeed. And Kwanzaa would be her keystone.

“The way [Kwanzaa at MBU] is set up, as an incoming student, it gets you connected and working with peers, alumni mentors, and OIE staff [typically within the first week of school],” said current Kwanzaa director Jaliyah Bryant ’23. That helps ease anxiety around transitioning to college, “because not only are you making new friendships from day one, you have alumni [like Tiffany Forman], and staff members like Rev. [Cornett-Scott] assuring you they’re there to help you every step of the way. And you can tell they aren’t just saying these things — it’s something they passionately believe in; their sincerity is obvious.”

Having no alumni base to draw on, Cornett-Scott initially tapped Black professors and local leaders in the African American community to serve as mentors for Kwanzaa at MBU ceremonies. They brought an element of lived experience to the program, and helped students internalize the fact that they would, in time, become the mentors of tomorrow.

“Here were these highly successful Black men and women volunteering their time to help you, and invest in your success,” said Foreman. “It made me think, ‘They have to see something in me, maybe I really do have something special.’”

Those seeds of confidence were nurtured as students tackled tasks that took them outside their comfort zone. Peers might encourage a shy but talented classmate to perform a vocal solo. A young man who was routinely scolded for being inattentive to detail might learn to sew intricate patterns for gowns made from ceremonial African fabrics. Others helped handle budgets and source materials from overseas. Still others learned complex dance sequences.

“When my parents came to watch my first Kwanzaa, they couldn’t believe it,” said Foreman. “They were like, ‘Who is this person, and what have they done with my daughter!’”

Student experiences almost universally mirrored Foreman’s.

“When the crowd started clapping and cheering, I looked around at my classmates and understood that we’d grown so much — we’d helped one another transform into totally different people from when we started,” said Bryant, recalling her first Kwanzaa at MBU. In that moment she suddenly saw herself in a different light: “I’d become the person that Rev. [Cornett-Scott and OIE alumni] had seen inside of me and been trying to draw out.”

From left: Tiffany Foreman ’04 posing with her family, Jaliyah Bryant ’23 rehearsing for Kwanzaa at MBU 2022.

The power of the experience — and the gratitude it induced — left participants insistent upon giving back. As the years passed, Kwanzaa alumni formed a network that spanned the U.S. They stayed in touch and Cornett-Scott routinely referred like-minded students to them for personal and professional guidance. Connections were strengthened during visits to campus.

“The friends I made working on Kwanzaa are now part of my family,” said Foreman. “My kids call them auntie, and I think of their kids as my nieces and nephews. … I come back [to MBU] each year because I know what participating in Kwanzaa meant for my life. I want to honor that gift by helping to make a similar impact on the lives of others.”

For Bryant and Meyer alumni like Foreman offer a looking glass into their future, a guiding light for a life well lived. And Cornett-Scott?

“To me, year after year her actions have shown us what it means to give yourself to a cause you believe in with all your heart, and how to live a life of meaningful service,” said Foreman. “It’s our job to take up that mantle. The message is: These lessons we learned at MBU? We have to take them out into the world and pour them into others the way Rev. [Cornett-Scott] poured them into us.”

While Cornett-Scott appreciates the praise, she’s quick to point out that the lesson Foreman describes is nothing new. She first quotes an African proverb, known as ubuntu, which has been read aloud at each of MBU’s Kwanzaa celebrations for the past 25 years: “I am because we are, and since we are, therefore I am complete.”

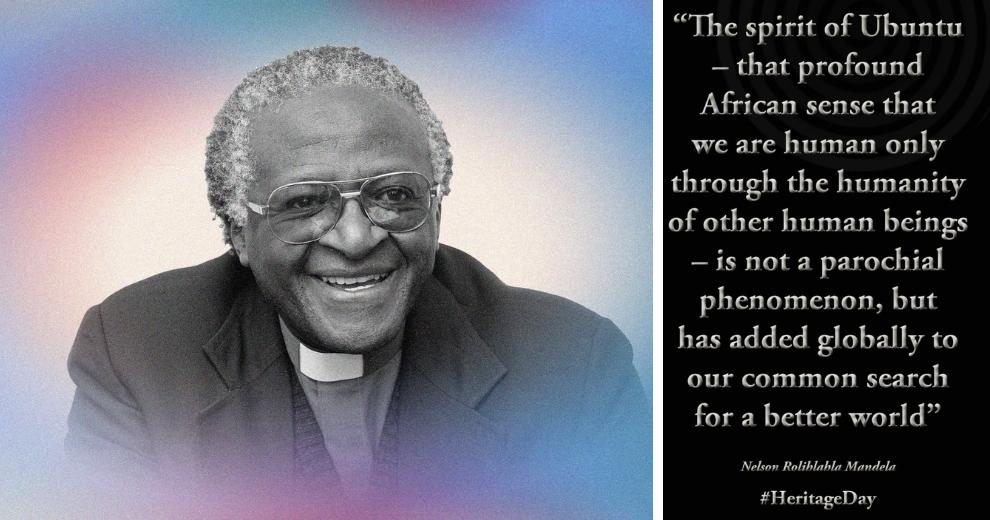

Next, she quotes famed South African theologian and Nobel Prize recipient Desmond Tutu.

“Ubuntu is the essence of being human,” he said in his 1984 Nobel acceptance speech. “It speaks particularly about the fact that you can’t exist as a human being in isolation. It speaks about our interconnectedness. We think of ourselves far too frequently as just individuals, separated from one another, whereas you are connected, and what you do affects the whole world. When you do well, it spreads out; it is for the whole of humanity.”

This, says Cornett-Scott, is what Kwanzaa at MBU is all about: When you positively impact the life of one person, it creates a ripple effect that uplifts the lives of countless others.

South African Nobel Laureate Desmond Tutu and a quote from fellow activist Nelson Mandela explaining the power of Ubuntu.

THIS YEAR’S KWANZAA AT MBU is part of the Office of Inclusive Excellence’s 25th anniversary celebration. CLICK HERE to learn more about additional special events.